- Home

- Debra Mares

The Mamacita Murders Page 10

The Mamacita Murders Read online

Page 10

“I know what a hymen is, but what is that other thing you just mentioned?” I ask.

“Sometimes it’s referred to as a fourchette. It’s the area right by the back area near the anus,” says Danielle.

Now she’s speaking in a language I can understand. I remember Neil telling me things I never wanted to hear about the fourchette. He used to joke, “Your fourchette is worth a fortune.” That’s the only reason I remembered the word.

When Neil worked in the delivery room during one of his stints as a resident during medical school, he said the fourchette can be torn during delivery because of all the stretching that goes on down there. To prevent this, the doctors would make a deliberate cut starting from the fourchette towards the anus.

Neil said when the cut went too far, it left the whole area way too loose to ever make sex enjoyable again. So Neil told me if we ever had kids, I would have to get a C-Section. The fourchette can also be torn with forced acts like rape and sometimes needs stitches to get it back intact. But Danielle said Laura didn’t need surgery and there was no bleeding, just inflammation.

“So are her injuries consistent with being raped?” I ask.

“No, not at all. They’re consistent with sexual intercourse in general. If she was violently raped, I’d expect to see more than this,” Danielle replies. “I’ll write my findings in the report. Here are all the samples. I hope you find whoever did this to her. But this girl wasn’t raped.”

Within one minute of Dylan and me leaving Laura’s room, sirens and a loud intercom announcement screams out, “Code Blue, fifth floor, room 5-1-1!” Dr. Lee comes running down the hall with Bess, who is being grabbed by one of the nurses.

I start running behind Dr. Lee and into chaos. Laura is being wheeled out on her bed. Nurses are running down the hall and loud sirens are screeching.

“Irregular heart rhythm!” screams one of the nurses to Dr. Lee, who is running down the hall. Sirens are making it hard for me to hear anything else the nurse says. But then I hear Bess screaming.

“Are we resuscitating, Doctor? There are no written orders,” yells a nurse.

“Don’t save her. She’s not to be saved! Those are my orders!” shouts Bess.

“I’m hearing the verbal DNR,” says Dr. Lee. “And we have a legal witness right here,” says Dr. Lee turning towards me.

“Save her, please save her,” I yell back.

Dylan grabs me by the arm, pinching me so hard it makes the nerves in my nose cringe. I unlock my arm out of his, scream at him to leave me alone, and continue rushing towards Laura. Dylan runs after me and pulls me into a waiting room closing the door behind us.

“What are you doing?” I yell.

“That is not your place to be doing this,” says Dylan, pushing me up against the wall.

“They’re gonna let her die. She can’t die. We need to save her. Please let me save her,” I say.

“Gaby. Stop. Calm down. Listen to yourself. You can’t save her. Let her go. This is not your decision. Stop trying to control this.”

I begin to sob uncontrollably in Dylan’s arms with him holding me. I can save her. We can save her. She can’t die. I need to save her.

“Shhh, Gaby. Calm down. It’s okay,” Dylan says.

Everything around me starts to look blurry like I’m looking through a hazy white film. My ears start ringing loud, my head feels warm, and I feel like I’m passing out.

I must have only lost consciousness for a couple seconds. I’m lying down on my back on the floor of the waiting room. The fogginess starts to clear up. I start focusing in on a television pinned to the wall showing some soap opera. I study the seats around the room that are attached to the floor and see Bess sitting in one of the seats. The coolness of a wet rag lying across my forehead sends chills through my body.

Bess reaches into her shirt and removes a black beaded rosary from her bra. She closes her eyes, bows her head, and begins to slowly move her fingers across bead after bead while mumbling.

“What happened?” I ask.

“I think you went into a little shock,” says a nurse crouched down towards me. She removes the damp rag from my forehead.

“I thought we were going to have to check you in. You turned from a bright pink to a ghost white in a matter of seconds. I was a little worried about you,” says Dylan.

“What happened to Laura?” I ask.

“Dr. Lee gave her a cocktail of drugs to calm her down,” says the nurse.

“Is she alive?” I ask.

“Yes. But she’s still in a coma. She does have a pulse, though,” says the nurse, smiling at me.

“She made it,” I say.

“Yes, she made it,” says Dylan.

“You got your wish,” says Bess, glaring at me.

“What are the drugs for?” I ask.

“Just to help out with her anxiety and stabilize her blood pressure. She was having an irregular heart rhythm that set the monitor off and triggered the Code Blue. It may have been triggered by the exam,” says the nurse.

“But I thought she couldn’t feel anything,” I say.

“We don’t really know what she’s experiencing right now. And it’s just in case,” says the nurse.

“I thought you guys were going to let her die,” I say.

“She pulled through this one, all on her own. She’s a little fighter,” the nurse says.

“Can I go see her?” I ask.

“Of course. Do you feel okay?” asks the nurse.

“I’m fine. I just want to see her,” I say, reaching for Dylan’s hand as he helps me up. We walk to Laura’s room.

Standing next to Laura, who’s resting in her hospital bed, makes me wonder what she can hear or feel. She looks dead to me and her coloring is more pale than it was when I saw her less than an hour ago before her Code Blue. I ask Dylan and the nurse if I could be alone with her for a minute and they leave the room.

“I’m sorry I didn’t get to you sooner, Laura. I know if I went to that motel just a little earlier, I could’ve saved you. I’m sorry. I won’t let them kill you. I know you’re gonna make it. I will fight for you to the end. I won’t let them put you in a casket. I won’t let that happen to you, I promise you.” I stare at Laura and see my mom’s face in hers.

I stare at Laura hoping she’ll open her eyes and see me. “Laura, please don’t leave me. Hang in there. I need you to wake up and tell us what happened. I need your help. I need you to get better and testify in Javier’s trial, too. Don’t leave me and I won’t leave you. I promise to come back every day to check on you until you wake up.

“Let’s do this one day at a time, together. Heal yourself. I need you to promise me you won’t give up on life. I need signs from you that you aren’t calling it quits. I’ll be back tomorrow to check up on you and let you know what’s happening in the investigation. Please, please, live through today,” I whisper to Laura.

13

THE CRIME LAB

Less than an hour after Laura’s Code Blue, Supervising DNA Analyst Miranda Jules greets us with a fresh smile and youthful glow at the front lobby of the Crime Lab. Miranda would meet the qualifications to work on the TV show CSI. She doesn’t fit the crunchy scientist stereotype. She’s trendy and wears glasses like the rest of her colleagues; they’re Coach ones, giving her a Pippa Middleton style that comes through even with her white lab coat on.

“Hi, Ms. Ruiz and Dylan, it’s nice to see you again,” says Miranda. With Miranda having Dylan on a first name basis and winking at him, I’m instantly suspicious if he’s dated her. But I stop myself and remember to put first things first. I’m here for Laura, not to investigate Dylan’s dating history.

I clip my guest badge onto my suit jacket and am now authorized to walk the halls of this sterile laboratory with Miranda and Dylan.

“Thanks for meeting with us on such short notice,” I say.

“Of course, anything for Dylan, my favorite investigator. Dylan and I have worked on many case

s together. What was our last one? That home invasion over in Mason Valley?” asks Miranda.

“Yes. You did an amazing job on that case,” Dylan says, trying to butter her up.

“Miranda located one of the suspect’s DNA on a ski mask he left at the crime scene. That was the only piece of evidence we had linking that guy to the scene.

“She built a profile within forty-eight hours on the case. She even stayed the weekend. I remember coming into the lab over the weekend to get the results. If I trust anyone with my cases, it’s Miranda. We’re in good hands,” he says.

“Aw. You’re sweet. Thank you, Dylan. Let’s go down this hall,” says Miranda endearingly.

I grab onto my guest badge like it’s my security blanket, making sure it’s still in the same place I clipped it thirty seconds ago. I can’t stand hearing Dylan and another woman gush over each other’s case victories right in front of me. Remember, Laura, Laura, Laura. This is all about Laura.

The Tuckford County Crime Lab, when under time pressure from my office, can analyze DNA found at a crime scene in two to three days if they’re pushed. Usually, it’s all based on case priority. If you have a good relationship with the crime lab supervisor and get him or her on your side convincing them the case is important, they’ll work hard to get the job done. They’ll even work over the weekend to help you, like Miranda.

The Crime Lab is over-flooded with work. A piece of crime scene evidence can sit at the laboratory for years before a criminalist takes a look at it, finds a DNA profile on it, then uploads it into a criminal database with offender DNA profiles — and possibly finds a match. The more serious the crime is or high profile the case is, the greater chance you have at the criminalists working up your case.

If you saw their meticulous notes and sterile lab, with all the quality assurance measures they go through to look at one piece of evidence, you’d understand why it takes so damn long. They aren’t just running a black light over the piece of evidence like you see on television. There’s a whole bunch of procedures they need to follow to make sure they keep up with standards and regulations of the state. I know Miranda can get the DNA done in Laura’s case if I can find a way to convince her.

“Why don’t we make a right down this hall and use this conference room to discuss the case? I think I read about it this morning in the paper,” says Miranda.

The medium-sized conference room gives me room to spread out my file. Dylan places his Special Homicide portfolio on the table and stares at Miranda.

“Is this the one where a young girl was found bound in the motel room, but she’s still alive?” asks Miranda.

“Yes,” both Dylan and I reply in unison.

“I’ll let Gaby tell you about the case. She has a personal relationship with the girl. She has been trying to recruit her into her club, so the news was shocking. They met in another case we were prosecuting. Laura is the victim in a sex case,” Dylan explains.

“Did the lab do any DNA work in that case?” Miranda asks.

“No, she didn’t report the sexual abuse until months later. There was nothing to test,” I say.

“Okay, well, tell me what pieces of evidence we have in the current case,” says Miranda.

What I’ve learned about DNA cases and the Crime Lab is that sometimes it’s better to give them less information about the facts of the case or the suspected perpetrators. It helps keep them unbiased if they don’t know whose DNA we hope they will find. When they are testifying and the defense is trying to make them look like our puppets, it helps when they know little about the case or the suspect. They can say they just were given items of evidence and looked for semen or fluids and figured out whose DNA it was. When they can testify they had little or no information about a certain case or suspect, it shuts down any potential defense of bias in our favor.

“We have a belt,” I tell her.

“Where was that found?”

“Around her wrists. Her hands were tied up and she was lying on the bed.”

“Was she tied to the headboard or any part of the bed?”

“No. Her hands were tied together and resting like this,” I say, holding my hands down by my lap.

“Were they tied to any other part of her body?” asks Miranda.

I shake my head back and forth. “They weren’t tied to anything. She was blindfolded, though,” I say.

“With what?”

“A sock.”

“Was she found lying face up or down?”

“Up.”

“What else do we have to examine?”

“We have a ceramic vase.”

“Why is that important?”

“It has blood all over it.”

“Where was that found?”

“Next to the victim.”

“What condition was it in?”

“Partially broken,” I say.

I used to make pottery when I was young. The hum of the wheel and the touch of the cool clay after dipping my hands in the water and kneading my clay always felt so soothing. I made my mom a vase one year. She loved it. My mom would wake me up every Saturday so we could pick roses from our garden and put them in our vase. I would do anything to hear her sing one more time, “Rise and shine and get some glory glory.”

One time, my stepfather cut our Saturday ritual short when he saw my mom talking to our neighbor John. I could still smell the alcohol on his breath when he stood over my mom at the kitchen sink as she filled our vase with water. I can still hear the crash of the vase when he shattered it against the wall. The white walls of my hallway spun around me like a moving tunnel as I ran to my room for cover that day.

“Ms. Ruiz, did you hear me?” asks Miranda.

“No, I’m sorry. What did you say?”

“Is there any other evidence you’d like examined?”

“Yes. Let me think,” I say. “There are exams from the suspect and the victim, who by the way is named Laura.”

“Was there any other evidence collected around the scene that might tell us who was there? It seems quite a task for someone to do this alone. I read in the newspaper that the entire room was ransacked in addition to the girl being tied up and her panties were pulled down to her ankles. Is that accurate?” Miranda asks.

The thing about news reports on crimes is they rarely report the details of crimes under investigation. Sometimes the media gets more information about a case than I may initially have. They are good about going into the community and interviewing people about the suspect or the victim. They will show up at memorial sites and take the time to speak with the people who are affected the most.

When it comes to details of the crime scene, however, they rarely have any. They are usually not allowed beyond the yellow crime scene tape or given much information by police, so the investigation is not jeopardized. Prosecutors can’t even give any more information to the press other than charges a suspect is facing, the maximum sentence a suspect is facing, and any other public information that takes place in open court on the record, like court rulings, testimony, and motions. Law enforcement never releases details other than the location something occurred, the suspect’s name and the victim’s name, assuming she’s not a minor.

“Was that really in the paper? That the room was ransacked and about her panties?” I ask, surprisingly.

“Yes, that’s what I read,” says Miranda.

“I wonder where they got those details. I’m surprised because they’re actually true,” I say.

“Those are typically things law enforcement would not release, especially this early in the case,” Dylan says. “I know I didn’t release that information and I can guarantee Ford wouldn’t have released that. The press release from the Leafwood Police Department didn’t contain that information, either.”

“Ms. Jules,” I begin. “I know how swamped the Crime Lab is. Every case I send here seems to take three to six months. But this case is very personal to me. I was prosecuting Laura’s sex case when she didn�

��t show up to testify, and then we found her in the motel.

“I was trying to recruit her into The Mamacita Club where I mentor at-risk women like Laura. Helping them is my passion. They come from broken homes, low income neighborhoods, and mobile home parks. They’ve been subjected to violence, gangs, and drugs. Laura is sitting in a coma over at the Memorial Hospital and can’t tell us what happened to her. We need science to tell us. This is an important case.

“I brought some pictures taken during one of our field trips. Laura’s best friend Christina is in this one,” I say, pushing one of the photos I printed on my desk jet printer early this morning towards Miranda.

“Who’s this lady?” asks Miranda pointing to the woman we visited.

“The girls met a cancer survivor whom they really bonded with,” I reply.

Miranda studies the photo with an expression that seems to recall something inside of her.

“This picture is what Laura looks like now,” I say, handing her one of photos taken by a tech yesterday.

Miranda looks at the photo and points to the horseshoe on Laura’s shaved head.

“I’m assuming this is from brain surgery?” Miranda asks.

“Yes, but for the grace of God, she didn’t die. Whatever you can do to get this DNA processed within the next forty-eight hours, it would mean a lot to me,” I say.

“The person you have in custody is her boyfriend, is that correct?” Miranda asks. “I read that in the paper, too.”

“Right,” I say. “Well, it was more so her pimp. We believe he was pimping her out from that motel room.”

“Why would her boyfriend or pimp have ransacked the room?” asks Miranda.

“That’s a good question,” I say, looking at Dylan.

“It’s pretty common for a suspect to make the scene look like a burglary occurred,” Dylan replies. “They do it to throw off the police and make it look like a random act. Or, the perpetrator, even when they know the victim, shuffles through the drawers looking for money or other things to take. Criminals are just greedy. They’ll grab things near the exit door of a store they just robbed. Some are just freeloaders, especially someone like Clown.”

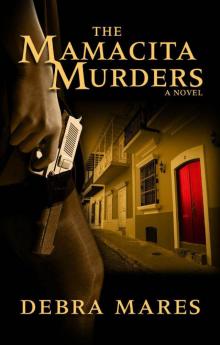

The Mamacita Murders

The Mamacita Murders